Electra-fying!

“This is not a play for the faint hearted.” Felix Peckham sits in on a rehearsal of this immersive and emotionally-charged production of Sophocles’s Electra

In an unassuming conference room in the heart of Robinson, I observe the actors rehearse and run through the second act of the BATS production of François Charmaille’s adaptation of Sophocles’s Electra. The room may be soulless, but the cast are anything but. The energy and tension among the characters fills the room, and the subtlety of their action only highlights the moments when they lose control, emphasising perhaps their desire to keep hold of what is slipping though their fingers.

Electra centres on the death of the eponymous character's father’s brutal murder by her mother, Clytemnestra and her new step-father Agisthus. The play then follows Electra’s struggle and desire for revenge, as well as her pain in grieving the loss of her father and the abandonment of her brother, Orestes. “She’s not just angry at the world,” says Grace England, who will be playing Electra, in response to the notion that she is often played the moody teenager, “she’s incredibly depressed and detached”.

The actors certainly seem to have taken the notion of grief and love being at the centre of the play to heart. In the few scenes I witness, both Clytemnestra (Elizabeth Gibbs) and Electra were in tears, leaving me unsure to whom I was supposed to align my sympathy. “Very few plays” says François to my questioning of the relevance of Electra to a contemporary audience, “have since had the balls to speak so immediately about the most taboo feelings we have for each other.”

“She speaks the unspeakable” concurs Grace, “she’s quite a terrible, furious character, but she’s quite relatable”. In truth, from my brief experience of a few scenes, still yet to be fully realised as they shall be on Thursday evening, Grace’s sentiment could describe all of the main characters; “quite terrible, quite relatable”.

It is a play of duality and contradiction where love and hate drive the plot in equal measure. Clytemnestra is evil, yet pitiable, Chrysothemis (Olivia de Hennin) is both survivor and traitor, Orestes (Fieke van der Spek) is hero and coward and Electra is victor and victim. And so the play explores the breakdown in family life - perhaps the most dependable yet fragile aspects of most of our daily lives. Although perhaps in this case, as is the way with Greek tragedy, this is taken to the extreme – a small, suffocating world where everything is spinning out of control.

This is not a play for the faint hearted, but neither is it promising to be a “museum exhibit”. Of course, the excitement and tension could be wasted come opening night, but the promise from the director to expect to be “really fucking terrified” gives me hope that this production of Electra should live up to my expectations.

If you feel your Lent term hasn’t quite tipped you in to the ideal state of bitter anger and fear, then I would recommend you give Electra a go. It might just make you forget about that last supervision.

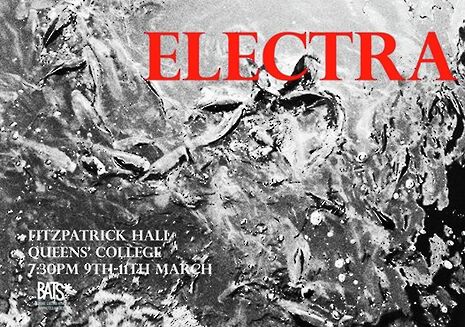

Electra runs at Fitzpatrick Hall, Queens' College, 9th-11th March at 7:30

Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024

Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024 News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024

News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024 News / AMES Faculty accused of ‘toxicity’ as dropout and transfer rates remain high 19 April 2024

News / AMES Faculty accused of ‘toxicity’ as dropout and transfer rates remain high 19 April 2024 Theatre / The closest Cambridge comes to a Drama degree 19 April 2024

Theatre / The closest Cambridge comes to a Drama degree 19 April 2024 News / Acting vice-chancellor paid £234,000 for nine month stint19 April 2024

News / Acting vice-chancellor paid £234,000 for nine month stint19 April 2024