Zika virus: global emergency?

The worrying virus is hitting the headlines

Unlike its related counterparts in the virus family Flaviviridae, the Zika virus does not have the luxury of a petrifying title. Yet the Zika virus, with only its exotic-sounding name to bear, is alongside Donald Trump on the sensationalist headlines of most American newspapers.

The Zika virus is spreading like wildfire, and it does not appear to be stopping its juggernaut-like invasion anytime soon. Once a virus restricted to the narrow equatorial belt from Africa to Asia, it was a virus unknown to the Western hemisphere until it started spreading eastward across the Pacific Ocean to French Polynesia, then to Easter Island and, in 2015, to Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, and South America, where the outbreak has reached pandemic levels.

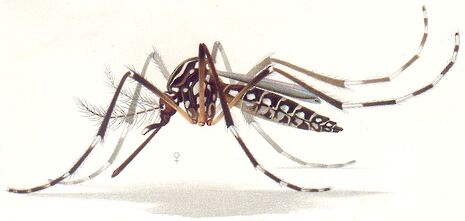

Like some zoological viruses that affect humans, mosquitoes (specifically Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus) are friendly hosts to the Zika virus. We expect that the geographic distribution of these pesky insects should be similar to the incidences of Zika virus infections, and indeed this is the case. The problem is, therefore, that these mosquitoes are extremely versatile breeders and are prevalent in hot regions. With objects that hold even the minutest amount of water, you can bet that the Aedes mosquitoes are dining and courting like all hell let loose in a Shangri-La hotel.

If the Zika virus was simply as harmless as an attention-seeking friend, then there would perhaps be no cause for alarm. However, there is very strong evidence that the rise in the Zika virus is associated with birth malformations and neurological syndromes in affected individuals. Newborns with reduced head size, a symptom of a neurodevelopmental disorder called microcephaly, are often born from infected mothers. Numbers rose from 147 cases in 2014 to 2,782 cases before the end of 2015. Coincidentally, 2014 was also the year that the FIFA World Cup was held in Brazil, during which the Zika virus is thought to have made its entrance. The Zika virus is also strongly associated with an autoimmune disease called the Guillain-Barré syndrome, where the body’s immune system perceives one’s own peripheral system to be dangerous and starts launching a ceaseless chemical offensive against it.

If the Zika virus does not have the capacity to cause a worldwide pandemic, we can perhaps be a little less worried. Yet, we do need to bear in mind the recent Ebola crisis where the World Health Organisation (WHO) failed to implement efficient measures and did not announce that the Ebola virus had caused a pandemic. This inaction led to thousands of preventable deaths. A healthy amount of worrying commensurate to the degree of virulence of the viral agent is required. The United States Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has issued a Level 2 travel alert for people travelling to certain countries where the transmission is ongoing. It also announced 31 cases of Zika infection among US citizens who travelled to areas affected by the virus, including the first case of sexual transmission of the virus. However, the Aedes aegypti mosquito vector is common in the US only in Florida, along the Gulf Coast, and in Hawaii, although it has been found as far north as Washington, D.C. in hot weather. So even if infected individuals return from an overseas trip, the mosquito vector may not be present to cause human-to-human transmission in the United States.

There are no vaccines available for the Zika virus, despite their availability for other flaviviruses. Nikos Vasilakis, of the Centre for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases, predicts that 10 to 12 years may be needed before an effective Zika virus vaccine is available for public use. With the virus causing largely asymptomatic infections, many people may be affected carriers and not know of their condition. This is compounded by the fact that efficient diagnostic measures are still not in place, given our limited knowledge of the Zika virus. The best we can really do at this point is to protect ourselves against these mosquitoes through the religious use of insect repellents and attempting to clear sites of stagnant water, as with any generic mosquito-borne viral disease. However, with the Summer Olympics to be held in Rio de Janeiro, the second-hardest-hit region in Brazil, it seems that stopping the Zika virus will require a lot of scientific progress and political gamesmanship.

News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024

News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024 Theatre / The closest Cambridge comes to a Drama degree 19 April 2024

Theatre / The closest Cambridge comes to a Drama degree 19 April 2024 Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024

Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024 News / AMES Faculty accused of ‘toxicity’ as dropout and transfer rates remain high 19 April 2024

News / AMES Faculty accused of ‘toxicity’ as dropout and transfer rates remain high 19 April 2024 News / Acting vice-chancellor paid £234,000 for nine month stint19 April 2024

News / Acting vice-chancellor paid £234,000 for nine month stint19 April 2024