Documentary: Bitter Lake

Masterful in its scope, and its humanity, says Chloe Carroll

Adam Curtis has been both praised and ridiculed for his innovative style, patching together short fragments of BBC archive footage, which he spends weeks trawling through, and compiling a collage of clips that range from the comic to the affecting; the bizarre and dream-like to the brutally real. It has been said that his technique obscures the facts; indeed, this blurred and flickering mass of footage amounts to something rather hypnotic.

Watching his newest documentary, released on iPlayer so as not to be restricted by the rigid schedules of television (it runs for an exhausting two hours and 20 minutes), one may be lulled into a sort of trance by the shimmering and contrasting visuals. This is not, in my opinion, to a negative end. The effect is brilliantly kaleidoscopic and often beautiful. More often, it is unsettling, with footage from Carry On... Up the Khyber placed alongside harrowing clips of US Marines revelling in their slaughters. Furthermore, the images are accompanied by an eclectic soundtrack, which spans from David Bowie to Kanye West, creating an effective juxtaposition of culture and era – footage of traditional folk dance is set to West’s ‘Runaway’ and an elegant harp plays over pixelated night-vision footage of a menacing helicopter, hovering like a wasp.

In short, Bitter Lake’s narrative is an attempt to uproot the oversimplified stories that we are told by politicians and the media: “Once upon a time,” Curtis begins, in sardonic fairy-tale fashion, “politicians told confident stories that made sense of the world.” Now, “we live in a world where nothing makes any sense. Events come and go like waves of a fever, leaving us confused and uncertain. Those in power tell stories to help us make sense of the complexity of reality. But these stories are increasingly unconvincing and hollow.”

His assertions are confident and often appear brash, like those of a conspiracy theorist. He has been accused of a narrative simplicity akin to that which he claims to debunk, and of igniting controversy for the sake of contrarianism. Bitter Lake, however, is enchanting and informative. It makes a lot of sense of a perplexing period in our history, the events of which are, for so many people, limited to disjointed fragments of TV journalism on BBC Breakfast.

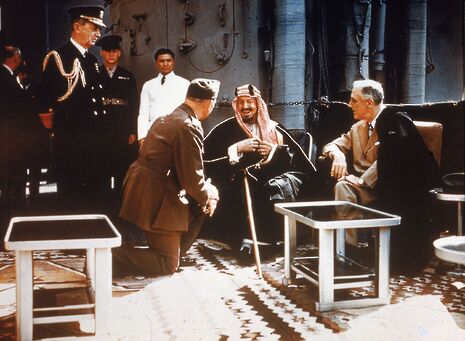

This limited, warped viewpoint from which the modern world suffers is expanded into a vast map of previously unobserved patterns of events and political deals. Curtis traces the conflicts between the West and the Middle East to a single deal made aboard a yacht on Bitter Lake by Roosevelt and King Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia, in 1945. The US was to support the recently formed state in return for an ongoing supply of oil: a complex relationship began. At one point the film turns to footage of a group of British students travelling through Afghanistan. The camera zooms in as they climb a flight of stairs onto a sandy stone promontory, then retreats into the distance, revealing the stunning cliff-face dotted with caves and the (now destroyed) Buddhas of Bamiyan atop which they stand.

This is, in a way, the structure of Curtis’ film-making; as he readjusts the perspective of our narrow lens, he reveals the detailed network of interrelated patterns which come together to form a new whole. While, in the midst of the conflict, those involved suffered an often misinformed and myopic vision, Bitter Lake surveys these sequences of events from above, forging telling links and associations: an artificial dam funded by the US irrigates the surrounding poppy fields, giving way to a multi-million dollar heroin trade, for instance.

Within this inundation of surprising facts and particulars, however, Curtis is sure to remind the viewer of the underlying humanity of those caught in the conflict. A grinning Afghan man dances for the camera, revealing a flicker of the joy and pride he takes in his culture; a group of children perch on a lakeside rock, their myriad expressions of distrust and delighted curiosity brought into focus.

In one particularly touching scene, a soldier sits among the bushes like a huge tortoise in his hefty camouflage, with a look of utter delight as a small bird settles on his gloved hand. He tentatively strokes it, gazing in mute disbelief at the camera in this moment of small joy, perfectly still in fear that the bird will be frightened away.

In a world so riddled with clashes of culture and belief, saturated with images of war, it is increasingly important to see beyond the hollow stories and simplifications we are presented with by the media and by politicians. Curtis aims through his use of archival footage, seemingly unintended in many cases for broadcast, to zoom out to a wider perspective. But he also zooms in, to the human and the sentimental, highlighting the individuals within the masses. Bitter Lake may assert a lot that it does not have time to necessarily back up, but it is masterful in its scope, and its humanity.

News / Police to stop searching for stolen Fitzwilliam jade17 April 2024

News / Police to stop searching for stolen Fitzwilliam jade17 April 2024 Interviews / ‘It fills you with a sense of awe’: the year abroad experience17 April 2024

Interviews / ‘It fills you with a sense of awe’: the year abroad experience17 April 2024 News / Night Climbers call for Cambridge to cut ties with Israel in new stunt15 April 2024

News / Night Climbers call for Cambridge to cut ties with Israel in new stunt15 April 2024 Sport / Kabaddi: the ancient sport which has finally arrived in Cambridge17 April 2024

Sport / Kabaddi: the ancient sport which has finally arrived in Cambridge17 April 2024 Features / Cambridge’s first Foundation Year students: where are they now?7 April 2024

Features / Cambridge’s first Foundation Year students: where are they now?7 April 2024