A game of tutors

A year on from CUSU’s campaign to instigate tutor training, Sarah Sheard explores whether chance still plays a role in being assigned a competent tutor

It seems a truth universally acknowledged in Cambridge that tutors are consistently inconsistent. For every positive story about a tutor providing valuable assistance to a student in hardship, there seem to be 10 anecdotes involving impassive, unhelpful or obstructive tutors.

I’ve developed this hypothesis from seeing the testimonies published by student campaigns such as Cambridge Speaks Its Mind (CSIM), but also from my own experiences with tutors.

In my first year, I had a tutor I can only describe as utterly disinterested. My first, and only, meeting with him lasted barely two minutes; he was the last person I would have gone to in a crisis. Luckily there were alternative forms of support available within my college, and in my second year I was reassigned to a more approachable tutor.

Personal experiences aside, it is clear tutors have always been subject to criticism in Cambridge; CUSU ran a successful campaign to introduce training for all new tutors in 2014, hailed as “a win” by then-Welfare and Rights Officer Helen Hoogewerf-McComb.

The training was obviously designed to combat an inconsistent system in which many tutors were only informally trained, if at all.

But the new training, implemented for the first time in October 2014, is not mandatory and only applies to new tutors. Inconsistencies would seem to remain, but is it just that the awful stories and testimonies are always more memorable, creating a biased image of the true state of tutors in Cambridge? Those stories are the ones, after all, that are posted on Facebook and widely shared, whilst someone who has a positive experience with their tutor is much less likely to shout it from the rooftops.

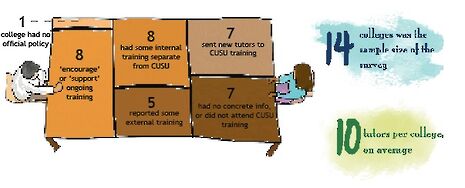

And so I took a representative sample of undergraduate colleges and asked how many tutors took the CUSU welfare training, and what the college’s policy is on training all tutors, as opposed to only those appointed from 2014. This, I hoped, would provide a broader idea of the consistency – or lack thereof – within Cambridge’s tutorial system.

It was immediately clear some colleges’ tutorial offices were far more organised than others. Some were unhelpfully vague; Clare admitted that none of their eight tutors had attended CUSU’s training but had undergone “informal training … on a weekly basis within College”, while Newnham cryptically said that “it is unknown how many of Newnham’s tutors went to [the CUSU] training day”, maintaining that all have had “some welfare training”.

Still, both Newnham and Clare were more helpful than the tutorial offices at Queens’, Peterhouse and Emmanuel, which, when asked how many tutors had attended CUSU training, replied mysteriously that they did not “hold this information”.

On the subject of training tutors in general, Queens’ described training as “desirable”, but added that they were “mindful of the pressures (academic & otherwise) which may reduce availability”. Peterhouse even stated that the college had “no specific policy” pertaining to training all tutors even once, let alone in terms of refresher courses.

Seven colleges sent their new tutors to CUSU’s tutor training, but equally, another seven could not offer me any concrete information. The phrase “the college encourages ongoing training” often cropped up in responses, but even this was referring to internal practice rather than anything standardised.

Girton, Homerton, Emmanuel, Fitzwilliam, Trinity, Downing and Clare all stated that their tutors have weekly meetings and/or informal training within college: but, crucially, there is no way to compare what ‘informal training’ means from college to college. Students are left at the mercy of whatever college authorities deem appropriate, leaving their welfare dependent on the college they attend.

Murray Edwards quickly emerged as the most well-equipped; the college runs fortnightly discussion groups to discuss welfare provision and also provides specific training for tutors on issues such as eating disorders and self-harming. Tutors are also specifically trained with regards to disabled students, while Cambridge Rape Crisis conducted a training session with the tutors, porters and nurse about supporting victims of sexual assault.

Amy Leach, a second year student at Murray Edwards, had an overwhelmingly positive experience after tearing her knee ligaments several times over the course of a year, describing her college as “extremely supportive”. The Senior Tutor, Juliet Foster, kept in “continual contact” by email and was able to co-ordinate taxis and a wheelchair to help Amy get around college and town. She also arranged for Amy to sit her exams in college and secured an exam warning for her.

“All in all I could not have asked for a more warm and supportive senior tutor,” Amy said. “In my view, she is a key reason why Murray Edwards continues to be such a caring and supportive environment.”

But it seems glaringly obvious that Amy’s positive experience was, at least in part, down to pure chance in being assigned a competent tutor. CSIM has countless anecdotes of unluckier students who have to cope with the added stress of unhelpful tutors, as well as welfare issues.

One student detailed in an anonymous testimonial that when she was suffering from depression and bulimia and was self-harming, her tutor told her to “think about how disgusting you are” and to stop herself purging, and said that she was jeopardising her friends’ welfare and exam performance, despite the tutor then revealing confidential details to these friends about her conditions.

The tutor also demanded to see the cuts from her self-harm before declaring her to be a “danger to the community”, justifying this with “if you do that to yourself, what’s to say you won’t go and cut somebody else’s arms up?”

Another harrowing testimony from CSIM was of a student who felt they were under “house arrest” after intermitting. Despite living in Cambridge their entire life, the student was informed by the Senior Tutor at their college that they “must not enter the University, the college, or any part of the city of Cambridge” and was even threatened with expulsion when they were spotted by a member of college staff on Trumpington Road.

Although a spokesperson for the university stated that “the University has no power to ban a student from the city or prevent them from living in Cambridge, especially if this is their main residence”, they could not comment on individual cases. The CSIM testimony concluded with the student remarking that they are “too afraid of losing my place at Cambridge to go any further than the end of my road”.

The veritable barrage of anecdotes at CSIM and similar campaigns is testament to the remaining disparities in the system. As one student linked to CSIM told me, “it’s impossible to know how ‘good’ a tutor is going to be at their job until they have been assigned to you.” Although he added the caveat that there is usually “a handful of decent tutors in each college”, the struggle lies in convincing colleges to re-assign a student from a bad to a good tutor during a difficult period.

The solution? Presumably honed from his CSIM involvement, the same student suggested that “all tutors should undergo training... not just new tutors, all of them”, adding that specific training should be included to support sufferers of mental health conditions, disabled students and survivors of sexual abuse, along with clearer guidelines on financial hardship.

Student feedback was also raised as an issue which is too often dismissed; “if a tutor receives enough negative feedback, they should step down from their position... their ability to support students should be paramount.”

For me, creating mandatory, centrally run training is a no-brainer. The utter lack of standardised training creates a dangerous lottery of whether your tutor will be capable of understanding and dealing with the problem in a way that preserves your dignity.

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024 News / Cambridge University disables comments following Passover post backlash 24 April 2024

News / Cambridge University disables comments following Passover post backlash 24 April 2024 Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024

Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024 News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024

News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024 News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024

News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024