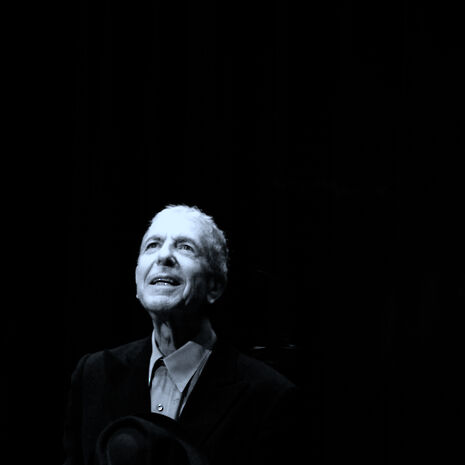

Obituary: Leonard Cohen

A Canadian musical icon dies at the age of 82

“Know that I am so close behind you that if you stretch out your hand, I think you can reach mine”. Six months ago Leonard Cohen wrote his last letter to his lover, friend and muse Marianne Ihlen. Then, in October, The New Yorker published a very long and detailed profile of him. Extremely laudatory but also crepuscular, it was the kind of piece that is only done just before or soon after a celebrity passes away. Finally, a couple of weeks ago You Want It Darker, Cohen’s 14th studio album, was released. The chorus of the first song, that gives the album its name, was composed of only five words, “Hineni/Hineni/I’m ready my Lord”. Cohen’s last message was clear, he was ready to die. And so he did, on 7th November 2016 at his home in Los Angeles.

82 years earlier, Leonard Norman Cohen was born in Montreal. His family was very active in the city’s Jewish community, where his grandfather played a patriarchal role. His father and uncle worked in the clothing business but Leonard aspired to be a poet. His first book was Let Us Compare Mythologies, a compilation of poems he wrote in college, published in 1956. Two more poetry works would follow as well as two novels. Yet living as a writer was as difficult then as it is now, and the bohemian life was not extremely appealing for a dandy-like Cohen. Besides, those were the years in which Bob Dylan had shown the musical industry that it was possible to combine poetry and popular music. Thus, Cohen picked up his guitar and gave music a shot. He was living in Manhattan, on the fourth floor of the Chelsea Hotel.

In 1966 he was spotted by Dylan’s producer John Hammond and the following year he released Songs by Leonard Cohen. Two years after came Songs From a Room, and it took Songs of Love and Hate yet another two years to see the light. Those three albums gained him a reputation as a songwriter who could compete with Dylan or Paul Simon. Yet it was 10 more years before he really become a cultural phenomenon. In the eighties, while the Sixties troubadours were silent, the Canadian singer created two masterpieces, Various Positions and I’m Your Man, that made him a true star. Cohen’s voice was deep and raspy, he started to work with synthesisers and his compositions became more rhythmic. He combined these new features with some of his trademarks, such as feminine choirs and truly poetical lyrics, and managed to find a style that quickly became his own. ‘Dance Me to the End of Love’, ‘Hallelujah’, ‘First We Take Manhattan’ and ‘I’m Your Man’ quickly became classics, and earned Cohen a special spot in popular music.

By contrast, the Nineties were very calm for the musician, and the new millennium was intended to be just as serene. Yet, in 2004, Cohen discovered that his manager had stolen money from him, an unfortunate personal situation that was beneficial for his fans: he had to tour and compose once again. Nobody could blame him if he wasn't been especially keen: he was broke and in his seventies. Yet, against all odds, he still managed to produce albums as good as Popular Problems and give passionate four-hour concerts until 2013.

All in all, it was a full career. And yet, deep down, in 50 years he only talked about three things: women, God and freedom. But Cohen’s women were not people, they were ghosts, ideas, phantoms. We know that some of them existed, thanks to his biographers, but it wouldn’t make a difference if they didn’t. In his songs, Marianne Ihlen, Rebecca De Mornay or Janis Joplin are no different from Nancy, the girl who killed herself in ‘Seems so Long Ago, Nancy’; Jane, who came back with a lock of his hair in ‘Famous Blue Raincoat’, or the unknown women who made him wonder in ‘Did I Ever Love You’. They were, as in most songs, abstract images over which the listeners could project their fears and fantasies. But what made him great was that they didn’t promise sexual satisfaction or conservative comfort.

His women were erotic figures that created a bridge between him and God. “The Lord is such a monkey/He’s such a woman too/Such a place of nothing/Such a face of you”. The Nobel Prize winner Bob Dylan once said that “Leonard’s always above it all,” because Cohen refused to write conventional love songs. He was wrong. He didn’t write them because he thought he was better, but because he understood that the feminine body was the strongest link between himself and the Maker. The only thing he was above of was bourgeois love. And deep down, we all share his view. That is why ‘Hallelujah’ has been covered more than 300 times. Because it makes us face pain and anguish and eventually realise that sex, love and God are but the same thing.

Without doubt, all these elements are the components for some of the most depressing lyrics ever written. But there’s always something redeeming in his songs: freedom. For him, the ultimate proof of the Lord’s love was to be found in our free will. In ‘The Partisan’, for instance, he sings about a resistant who’s surrounded by death and yet can find happiness in the fact that he remains free. It is also because of this liberty that he can display a very subtle irony. “And Jesus was a sailor when he walked upon the water/And he spend a long time watching from his lonely wooden tower/And when he knew for certain only drowning men could see him/He said all men will be sailors ten until the sea shall free them”. Those are not the words of a man browbeaten by God; they are those of somebody who has come to terms with the funny and bitter irony of live.

I discovered Cohen the summer before coming to Cambridge, in the opening credits of the second season of True Detective. His deep voice, the repetitive synthesiser, the menacing lyrics and the women in the background repeating “never mind” were probably the best thing about those otherwise forgettable episodes. I kept on listening to him and his compositions quickly became a fundamental part of my first year soundtrack. In fact, my best friend gave me a compilation of his poems and songs for Christmas. On the evening of 10th November, she was at my place with some other friends and asked me to play one of his songs, like I used to last year. I didn’t as the atmosphere wasn’t appropriate. Once they had left, I opened Facebook and saw a post announcing his death. I can only hope that the reaper found him as prepared as he told us he was

Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024

Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024 News / Controversy on the Cam: John’s spend almost 90 times more on rowing than other colleges19 April 2024

News / Controversy on the Cam: John’s spend almost 90 times more on rowing than other colleges19 April 2024 Theatre / The closest Cambridge comes to a Drama degree 19 April 2024

Theatre / The closest Cambridge comes to a Drama degree 19 April 2024 News / Corpus student left with dirty water for over six months21 April 2024

News / Corpus student left with dirty water for over six months21 April 2024 News / Emmanuel College cuts ties with ‘race-realist’ fellow19 April 2024

News / Emmanuel College cuts ties with ‘race-realist’ fellow19 April 2024