The Last Blog of Captain Scott

To mark the centenary of Captain Scott’s doomed final expedition, Katy Browse looks at new ways of telling an old story

Captain Scott knew that the race to the South Pole would be a hard one to win. What Captain he didn’t know when as he set sail in 1910 was just how close it would be.

He arrived at the Antarctic’s McMurdo Sound (the ice-clogged waters that are only accessible in summer temperatures) already aware that the Norwegian team led by Roald Amundsen was also heading south. The team of Norwegians would eventually claim the prize yet Scott’s team earnt a reputation as the brave, ambitious and ultimately tragic faces of polar exploration. Reaching the Pole but falling victim to the cold on their return, many miles from home, he was recognized as a British Hero.

Memorial donations for Captain Scott showed his country’s appreciation for the pioneer. It mattered less that he didn’t succeed and more that he died with dignity, as he says of his comrade, Captain Oates.

"He would not give up hope to the very end. He was a brave soul. This was the end"

'He said, ‘‘I am just going outside and I might be some time.” He went out into the blizzard and we went out into the blizzard and we have not seen him since.’

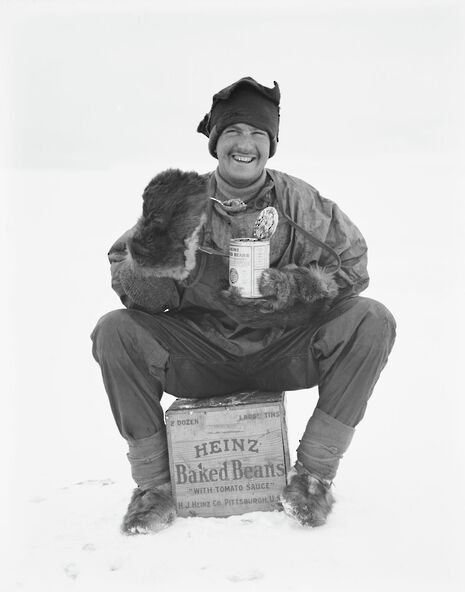

These quotations would not have survived without Scott’s diary. The Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, founded with the remainder of the funds raised on his death, is now retelling the story of these last fateful months in their exhibition: ‘These Rough Notes’. It is well worth a look, if not just for for its McMurdo miscellanies. Scott’s base camp, built to house the men for winter, was complete with stables for the arctic ponies as well as a dark room for its photographer. The work of this photographer, Herbert Ponting, deserves its own exhibition; Scott recognized a commercial opportunity and commissioned him to feature brands such as Lyle’s Syrup and Colman’s Mustard in his photographs. He offered to put their products next to that most exotic of creatures, the penguin. Most of the Ponting's photos are of the expedition itself but there appear among them some of the earliest examples of product placement.

The photographer was not present on the trip to the Pole. Nineteen set out with Scott, the supporting parties returned in stages and only four men went with Scott on the last leg of the journey, reaching their goal on 17th January. It is Scott’s diary that tells the story up tolast, with its final entry on 29th March 1912. The last volume of the diary is in the display, on loan from the British Library. SPRI has also put the text online.

If you visit their website, Scott’s day-by-day entries are blogged, and if you need a reminder that things could be a whole lot worse as you start term, they even tweet them.

Today we find the team fresh from defeat. Signs of bitterness in Scott’s diary? Perhaps.They have found signs of the Norwegians:

Friday, January 19, T. -22.6°: "Early in the march we picked up a Norwegian cairn and our outward tracks. We followed these to the ominous black flag which has first apprised us of our predecessors’ success. We have picked this flag up, using the staff for our sail, and are now camped about 1½ miles further back in out tracks. So that is the last of the Norwegians for the present.”

Amundsen, however, will be the least of Scott’s worries as he sets out on the return journey where they will meet with misfortunes that Scott names as individual ‘tragedies’. These will unfold all the way through February and March until the end of term. Scott was found just eleven miles from the next depot of food and fuel; the account of these months is emotional and poignant.

He would see one of his team severely concussed after a fall, another fighting frostbite, until the point that he and his men could only write letters to friends and loved ones and hope for the best:

Thursday, March 27th: "We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far.It seems a pity, but I do not think I can write more.

R. SCOTT.

For God’s sake look after our people.”

The Antarctic expedition had been advertised to potential officers as the chance ‘to reach the South Pole, and to secure for the British Empire the honour of this achievement’ and they failed to be the first to do so by just over a month. As the ‘Tate & Lyle’ anecdote shows though, there was more to the expedition than glory-hunting. Scott’s ambitions went beyond Amundsen’s. The 65 strong British team also included photographers, scientists and naturalists such as Edward Wilson, who died with him on the return journey. This, too, shows in the diary entries that are to come. On the hard trip back, Scott honours Wilson’s request for a scientific detour despite awful weather and dwindling supplies. Wilson wanted to look among glacial debris in the shadow of Mount Erebus. It meant that, found alongside the diaries of the pole parties was a prize fossil, the hitherto unknown plant Glossopteris Indica.

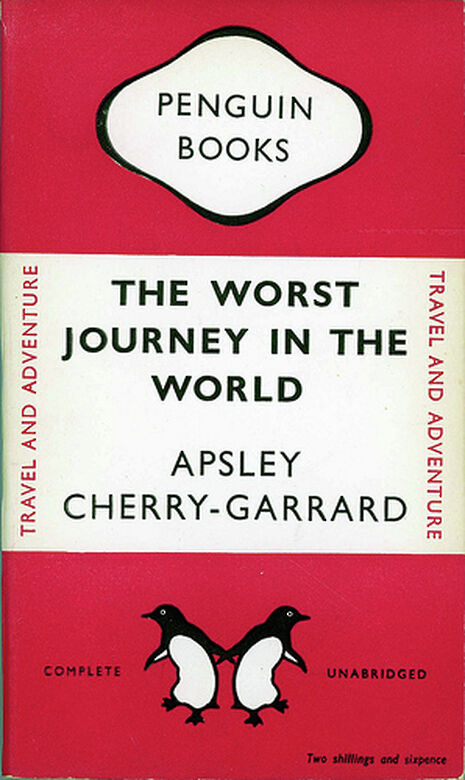

It was Wilson that had led a trip from the base camp that has gone down in history in its own right. Named The Worst Journey in the World, Cherry-Garrard’s account is recommended if you want another insight into this expedition. Current evolutionary theories, in which Wilson was absorbed, held the emperor penguin as vital. It was thought of as a missing link between reptiles and birds, and that the embryo passed through all previous evolutionary stages during the course of its development. Getting hold of its eggs then, was 'the greatest biological quest' of the day.

You can imagine that it took a lot of these statements at the Cape Evans base camp to coax his fellow officers into the trip. It meant that three men travelled into the Antarctic winter, during which no sun shines, trying to track down the breeding birds. The eggs were gold dust. They were successful (although the theory, unluckily, was not). From an advertising campaign to scientific ambitions that outlive him in the Institute named for him, Scott’s story is not just one of heroism. The diaries and letters show that he and his team had that which the Norwegians did not; a truly British grit, humour and eccentricity.

With thanks to the Scott Polar Research for help in developing this article. A review of The Worst Journey of the World can be found in the Literature Section.

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024 News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024

News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024 News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024

News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024 Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024

Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024 News / Emmanuel College cuts ties with ‘race-realist’ fellow19 April 2024

News / Emmanuel College cuts ties with ‘race-realist’ fellow19 April 2024