From Zimbabwe to Stamford: reflecting on my nationality

Moving from Zimbabwe to England as a child had caused our writer to reflect on the complications in understanding nationality

It was only recently that I learnt the word ‘diaspora’, describing a body of people who have dispersed from their country of origin to live in multiple different places, meaning that I have unwittingly been part of one for half of my life.

Growing up in a different country to the one in which you currently live creates a very unique set of experiences. There is no simple answer to the question, ‘where are you from?’. This might come with a complicated relationship with your accent, whether it is strikingly unusual, or whether it has evolved into something more conventional. Either way, it feels like it doesn’t fit - either with the voices around you, or with your personal history and self-conception. A certain desperation for the once-familiar leads you to have in-depth conversations with people you would never otherwise speak to, about politics you still don’t entirely understand and about places that have become sepia-toned in memory.

Having lived a multi-national life means that the constructed nature of nationality shows the scaffolding propping it up, provoking questions that are impossible to answer

This August marks the ten-year anniversary of my family’s move from Zimbabwe, 7,800 miles north to Stamford, a small town near Peterborough. Such a drastic change, in culture and in climate, was an absurd shock as a ten-year-old, but as time passes, my prior life becomes increasingly hazy. As memories become more like half-remembered dreams, so too does the concept of nationality itself, though bureaucratic forms simplify it to a drop-down list of options. Having lived a multi-national life means that the constructed nature of nationality shows the scaffolding propping it up, provoking questions that are impossible to answer.

Of course, it is an immense privilege for me to even pose the following questions about nationality in a theoretical framework, coming from a family which could escape the hyperinflation, empty supermarkets, and corruptocracy. The recent elections in Zimbabwe, that sparked hope swiftly descended into brutality and disappointment, suggesting that Zimbabweans hoping for democratic reform post-Mugabe might still have a long journey ahead of them.

Legally, nationality is defined by citizenship. Where is it that you are recognised as a citizen? What colour is your passport? Such a definition allows for minimal nuance, giving dual nationality to a select number of people but refusing to acknowledge the diverse potential of those who have criss-crossed the globe. I have always held a British passport, since my mother is British, but my birth certificate was issued by Zimbabwean authorities in Bulawayo. Different pieces of paper tell small parts of the whole truth, but bouncers and airport officials always quirk an inquisitive eyebrow at the place of birth registered on my passport and driver's licence.

Perhaps nationality is determined by your family history. Children often divide their identities into fractions, working out their heritage down to eighths and sixteenths. However, this too is overly simplistic, particularly for families with histories of immigration. Zimbabwe, previously known as Southern Rhodesia after the colonialist Cecil Rhodes, was a British colony, and my grandparents who moved there in the 1950s were Scottish and English, during a time when the country was still under white-minority rule. You cannot have a conversation about Zimbabwe without mentioning this colonial history, particularly when you are white, and therefore one small cog in the mammoth bulldozer of British imperialism. Though Zimbabwe is, technically, independent, the aftershocks of colonialism are still felt today in the language, culture, and power structures in the country.

If I were to fully claim an identity as a white second-generation Zimbabwean... it would necessarily include questions of empire, power, and complicity that are almost unanswerable

My grandparents’ children were all born in Rhodesia, before it officially gained independence as Zimbabwe in 1980, so are they then Rhodesian or Zimbabwean? And since those aunts and uncles diverged to live in different places across the globe, are they now Swiss, British, New Zealanders? I had always thought that my position in the second generation of my family to be born in Zimbabwe was fairly uncomplicated. But as I grew older and more aware of Zimbabwe’s colonial history (something, unsurprisingly, that my primary education there and secondary education here never covered), it became more complex. If I were to fully claim an identity as a white second-generation Zimbabwean, which would erase the last ten years of my life, it would necessarily include questions of empire, power, and complicity that are almost unanswerable. The tangled ends of nationality are no sooner unravelled than another potential answer leaves them coiled into themselves again.

The question mutates into wondering whether nationality is something you are born with, or something you become. Many countries require a process of ‘indigenisation’ before you can achieve citizenship, which is curious. Transplanting people into a new place does not magically endow them with the traits and traditions understood to belong to the native people, and there is a great deal of work which goes into becoming socially indigenous, regardless of your legal status. This can be magnified by various degrees of difference; if, like me, you are white, have a British mother, and speak English as your first language, the process is automatically far smoother, even if the it takes the edges off your Zimbabwean accent and allows you to blend in. But there are still complications with the concept of indigenisation. How long does it take to become indigenised? Can nationality be fragmented into fractions by the length of time spent in one place? I am twenty, and I have spent half of my life in Zimbabwe and half in England. If proportions are an adequate way to determine nationality, I have been mostly Zimbabwean up until now, but soon the balance will start to tip the other way.

I will always be sentimental about my Zimbabwean childhood, spent running around wild kopjes and avoiding deadly snakes

People often ask me "Where do you prefer?" This primarily implies a choice, but implicitly, an connection with one place that is somehow stronger or deeper to the other. If you have paid attention to the news from Zimbabwe for any length of time, at a more political level than the shooting of Cecil the lion, you will be aware that it is a challenging place to live, to say the least. On the most basic level, living in England offers some stability which the turbulent political situation in Zimbabwe could not. This is largely why between 500,000 and 4 million people have migrated from the country in the last ten years (Harare’s International Organisation for Migration office cannot be more specific about the figures).

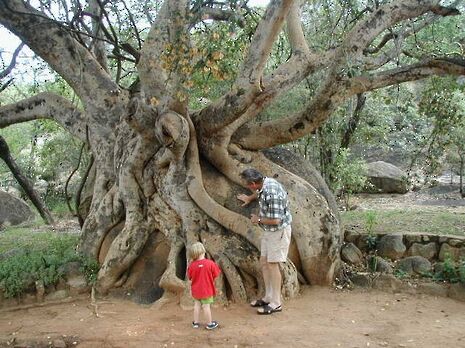

The question of preference is particularly difficult when the life stages passed in each country are so vastly different; being a child of primary school age in one place and moving through secondary school to university in the other hardly allows for a fair comparison. In any case, preference in relation to nationality holds little sway in any realm other than the emotional. I will always be sentimental about my Zimbabwean childhood, spent running around wild kopjes and avoiding deadly snakes, but census forms and curious acquaintances aren’t interested in the nuances of nostalgia. When people ask me in those moments of small talk about Zimbabwe if I’ll ever go back, I’ll say yes – it’s an immensely important, if largely invisible, part of who I am.

Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024

Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024 News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024

News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024 News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024

News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024 News / John’s spent over 17 times more on chapel choir than axed St John’s Voices22 April 2024

News / John’s spent over 17 times more on chapel choir than axed St John’s Voices22 April 2024 News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024