Is oversharing caring? Making the personal public

Finty Hunter explains how writing an online article about dealing with her father’s death has changed her interactions with people in real life

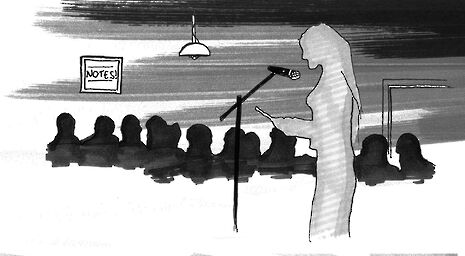

I write poetry. And by nature of writing poetry I share things about my life that I wouldn’t necessarily usually blurt out to people. I talk about love (classic), I talk about my feelings of grief, of inadequacy, of whatever thoughts I’m holding onto at the time I put pen to paper. None of my friends have ever questioned this, why I write such personal things and open it up to public consumption. When I read a poem at Notes about my dad only a couple of weeks after his death, I felt my voice crack over the lines, standing in front of a room of strangers – and the friends I had dragged with me for moral support – and pulling them into my memories, moments of domesticity and familial intimacy, those last weeks of my father’s life. I didn’t cry when I read it. That was my main aim, to not cry. For some reason I was okay with sharing my grief in words but not in physicality. My friends hugged me afterwards and told me it was beautiful. Someone told me that reading it had helped them with their own grief.

I recently wrote a Varsity article about the death of my father. I posted it to my Facebook wall and a fair few people I know – and some I didn’t know – messaged me about it. A common theme in these messages was people apologising if they were overstepping the mark, encroaching on my personal life by sending me messages of sympathy, of support, offers of help and understanding. It was these apologies that made me realise how uncomfortable some people feel with the notion of making your personal life public. I threw out my feelings of grief into the void that is the internet and left them out for people to step over, glance at, and intrigue themselves over. I revealed my grief to strangers. And I don’t know why there’s some kind of cathartic therapeutic nature to it, but there is.

“I realised then that for many people this was the first time they were really hearing the reality of what had happened”

I was opening up about some of the worst moments of my life, and, yes, of course I didn’t share every tiny detail, but I did reveal things that I hadn’t been able to say in awkward kitchen conversations in January when someone on my floor asked how my Christmas was and asked me why I had driven myself to Cambridge this term. After I wrote the article she messaged me and came up to me in the corridor and said that it was very moving. I realised then that for many people this was the first time they were really hearing the reality of what had happened.

It was here I realised the reality of sharing something so personal on something so public. And I don’t regret that. I’m a very open person, and that’s something I pride myself upon. Yes, I have things I don’t tell everyone, and I don’t share every little aspect of my life. But I am open about things: I’m honest. I’m not sure whether the article constitutes as ‘oversharing’, I guess that depends whom you ask. But I’m not sure I really care either. I wanted to express something that so many people go through but many keep secret. I am not ashamed to be grieving. Yes, I’ve only managed to write one essay so far this term when I should’ve written five but I’m not ashamed of that either. If no one ever talks openly about the bad things then how do you know you’re not the only one going through it?

The day the article was published I had a supervision. I stood on the staircase waiting to go in and there was another girl there. She looked at my friend and me with interest, clearly trying to work out where she knew us from – Cambridge is such a small place that that’s not exactly an uncommon experience. Whenever I walk down King’s Parade I’m accosted by memories of Life’s smoking alley and the Cindies dance floor. She asked me if I had written an article for Varsity about my father, I told her I had, she told me it was very moving and she struggled to know what to say to me.

Sharing is caring and so, I guess, is ‘oversharing’.

Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024

Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024 News / John’s spent over 17 times more on chapel choir than axed St John’s Voices22 April 2024

News / John’s spent over 17 times more on chapel choir than axed St John’s Voices22 April 2024 News / Corpus student left with dirty water for over six months21 April 2024

News / Corpus student left with dirty water for over six months21 April 2024 Theatre / The closest Cambridge comes to a Drama degree 19 April 2024

Theatre / The closest Cambridge comes to a Drama degree 19 April 2024 News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024

News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024