Dreadlocks, Marc Jacobs and white privilege

White designers sell minority culture as a commodity to privileged customers – under the guise of artistic license, says Emma Simkin

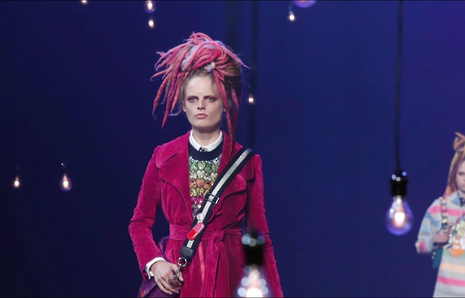

For fear of sounding like yet another white liberal crying “cultural appropriation”, I originally set aside writing an article on it. After so much discussion of it in the media, I assumed the message had been delivered. Yet, after the final day of New York Fashion Week, it seems the idea of cultural appropriation hasn’t hit home just yet. Criticism has erupted after Marc Jacobs used white models styled in colourful dreadlocks.

Perhaps the worst part is the 53-year-old designer’s defence. He has deflected the criticism as “nonsense” under the guise of creativity, stating that “appreciation of all and inspiration from anywhere is a beautiful thing.” His stylist Guido Palau is equally as ignorant. When asked directly about the ‘politics’ of the use of dreadlocks, Guido considered it a form of artistic expression. “I don’t really think about that,” he said. “I take inspiration from every culture.” It seems that the brand and others members of the fashion business still fail to recognise that calling out cultural appropriation is not inhibiting artistic license, but is challenging a harmful system.

There is a fine line between cultural appreciation and cultural appropriation, and one that the industry too often fails to notice that it is crossing. It is true that appreciating a culture may allow new creative insights. However, I don’t see how a white designer styling white models in locks can be considered cultural appreciation when the origins are not even acknowledged.

If a designer gathers inspiration from other cultures, this needs to be done with respect. This is not possible when the artist fails to acknowledge the cultural roots of the style. When asked for his inspiration behind the styling, Guido referenced 80s and rave style, but mentioned no people of colour. When a white designer employs a white hair stylist to hire a white women to yarn woollen dreadlocks without acknowledging black culture, it becomes hard to see how Marc Jacobs can claim “appreciation of all”. Failing to acknowledge the cultural origins of locks is failure to understand the discrimination people of colour face.

In a rather confusing attempt to deflect allegations of racism, Marc Jacobs commented: “I don’t see colour or race – I see people”. Perhaps without such colour blindness he would have noticed that his runway was but a display of shameless white-washing.

The fashion business consists mainly of privileged persons. White designers sell minority culture as a commodity to privileged customers under the guise of artistic license. Those who don’t benefit are the people of colour who are locked out of the same industry that appropriates their culture.

Black women with locks are faced with ridicule by the same industry that admires the style on white skin. At the 2015 Oscars, Zendaya’s hairstyle was ridiculed by Fashion Police presenter Guiliana Rancic, commenting that she must smell like “patchouli oil. Or weed”. When locks are worn by members of the culture of origin, they are deemed by the fashion industry as trashy, but when appropriated, it is seen as high fashion.

By praising locks on white people, but not those of colour, the fashion industry is saying that the racial feature is only beautiful when taken by white women. By predominantly hiring white women in an industry that supposedly epitomises attractiveness, whiteness is seen as a beauty ideal. In short, the modelling industry tells us that being beautiful means being white.

It is of course possible for British fashion to appreciate another culture, when white designers do not feel the need to claim it as their own. As spectacularly demonstrated in London Fashion Week by Dehli-born Ashish Gupta’s show, fashion can be a beautiful celebration of multi-culturalism. In a dramatic yet solemn show, his lineup of diverse models featured mythology-laden South Asian garments styled in a silhouette of Western streetwear. This blend of cultures within fashion makes a poignant political statement of social inclusivity, and is a true example of the beauty of multi-culturalism. Yet, if the same lineup were to be worn by white models under the instruction of a white designer, the statement would instead be one of exclusivity.

For the industry to appreciate rather than appropriate, cultures need to be treated with respect. This respect cannot be found in an industry that fails to acknowledge the roots of their designs, especially against the backdrop of Caucasian beauty standards. Creative flare is never an excuse. Calling out brands that appropriate does not inhibit artistic license. What the criticism does do is challenge traditional beauty standards that harm members of oppressed cultures.

Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024

Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024 News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024

News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024 News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024 News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024

News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024 News / John’s spent over 17 times more on chapel choir than axed St John’s Voices22 April 2024

News / John’s spent over 17 times more on chapel choir than axed St John’s Voices22 April 2024