Guggenheim Exhibition: ‘For Your Eyes Only’

Lavinia Puccetti discusses the seduction and persuasion that pervades the art of this intriguing exhibition

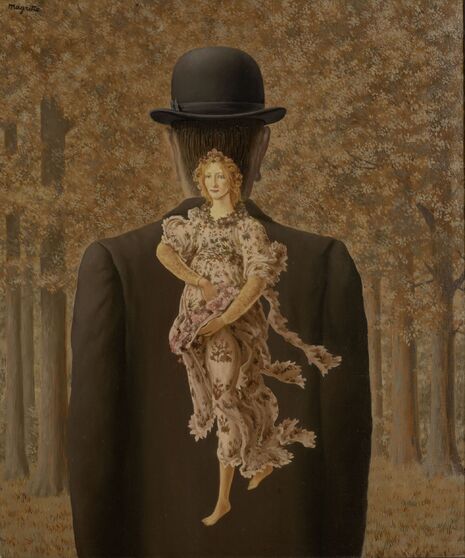

A man in a bowler hat turns away, looking into the spongy, ochre-iridescent leaves of an autumnal forest. A woman carries a bouquet while stepping out of the man’s black silhouette, as if in a painted collage. This is Magritte’s 1956 painting, The Readymade Bouquet, the picture that has been scattered across Venetian walls to advertise For Your Eyes Only. This exhibition at Venice’s Peggy Guggenheim Collection features and juxtaposes works from Mannerism to Surrealism. The exhibition displays the private collection of Swiss art lovers Richard and Ulla Dreyfus-Best and Margritte’s painting is its paradigmatic manifesto.

For Your Eyes Only recalls the eponymous 1981 Bond film and this exhibition is about a peculiar type of espionage: the aesthetic one. The man in the bowler hat is silhouetted in the shape of a keyhole at the bottom of which one finds Botticelli’s Flora. This visual trope synthesises the three key themes of the exhibit.

First, gender perception – a woman is seen through the shape of a man, highlighting centuries of artistic representation centred on the male gaze. Second, the dialogue between past and present – Flora belongs to the Renaissance and yet she is cut out and pasted over the man in a bowler hat, crystallising the exhibition’s playful juxtaposition of artworks across time. Third is the aesthetic fascination for the uncanny; the viewer goes from visitor to voyeur.

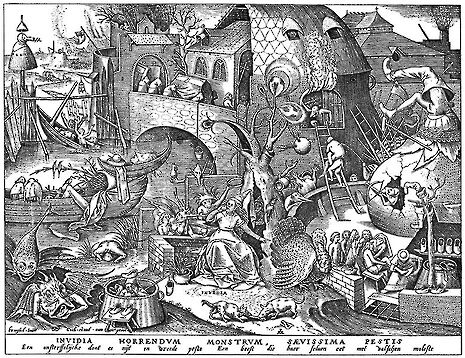

This exhibition consciously explores art's powers of seduction and persuasion. In Frans Francklen The Younger’s Witches Kitchen (1604) the onlooker becomes an accomplice of the witch. She exposes her leg, drawing the viewer closer into her pictorial sphere and towards the numerous daemons, tools, and sacrificial animals around the cauldron. A Flemish Master’s Allegory of Vanity encapsulates the semantic reversal: the artist excuses himself for painting lust, pretending to denounce it, while he is voyeuristically delighting himself and the viewer. Böcklin’s Shield with the Head of Medusa (1887) challenges the customary reading of her petrifying gaze by representing a woman who has herself been petrified by fear before death.

For Your Eyes Only does not shy away from exposing repressed emotions: Victor Brauner’s Psychological space (1939) depicts sexual desire and animalistic violence through a wolf-table that wishes to devour a woman already disembodied by fading spirits. Hans Bellmer’s Cephalopod (1900)plays with the representation of sexual intercourse, here metamorphosed into an inextricable body fusion, challenging sexual identification. His drawing Phallus Eye (1961) turns a face into a penetrated vagina. The provocative exposure and cathartic depiction of sexual anxieties – and fantasies – have been censored for much of art history, but now the Dreyfus collection embraces everything that is a mystery for our eyes.

This is a collection that encourages visitors to embrace espionage, both art-historical and aesthetic. In each room, the works are linked by visual nuance and by a shared taste, across different movements, for the uncanny and conscious appropriation of the erotic. In spying on the Dreyfus-Best collection, we spy on our aesthetic, unconscious self.

The exhibition is open until 31st August 2014.

News / Police to stop searching for stolen Fitzwilliam jade17 April 2024

News / Police to stop searching for stolen Fitzwilliam jade17 April 2024 Interviews / ‘It fills you with a sense of awe’: the year abroad experience17 April 2024

Interviews / ‘It fills you with a sense of awe’: the year abroad experience17 April 2024 News / Night Climbers call for Cambridge to cut ties with Israel in new stunt15 April 2024

News / Night Climbers call for Cambridge to cut ties with Israel in new stunt15 April 2024 Sport / Kabaddi: the ancient sport which has finally arrived in Cambridge17 April 2024

Sport / Kabaddi: the ancient sport which has finally arrived in Cambridge17 April 2024 Features / Cambridge’s first Foundation Year students: where are they now?7 April 2024

Features / Cambridge’s first Foundation Year students: where are they now?7 April 2024