To Thine Own Self Be True

From self-portraits to selfies, Nina de Paula Hanika traces the art of portraying the self

Selfie was the Oxford English Dictionary’s word of the year for 2013, and is officially defined as: "a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and uploaded to a social media website." So far, so Facebook. Selfies bred like bacteria in 2013, apparently by 17,000 per cent, and yet our faithful friend the OED goes on to add in its handy example: "occasional selfies are acceptable, but posting a new picture of yourself every day isn’t necessary." Ooof – cuts deep.

Criticised as endemic narcissism by Jonathan Freedland, lauded as the ultimate fourth wave feminist act and even explored in an 'essay' for the New York Times by everyone’s favourite pseudointellectual, James Franco, it seems the selfie wields enough power to make even the dictionary seethe. Yet, the self is a slippery fish that people have been attempting to pin down for years.

Prior to the invention of photography, artists were the only ones with the potential to provide a tangible image of one’s appearance, and with better mirror production techniques developed during the Renaissance, artists increasingly turned to the most convenient subject matter available: themselves. Several artists chose to return repeatedly to the subject of their own self over the span of their lifetime. The Dutch artist Rembrandt painted dozens of self-portraits over his career, beginning at twenty-two years of age and painting his last in 1669, the year he died.

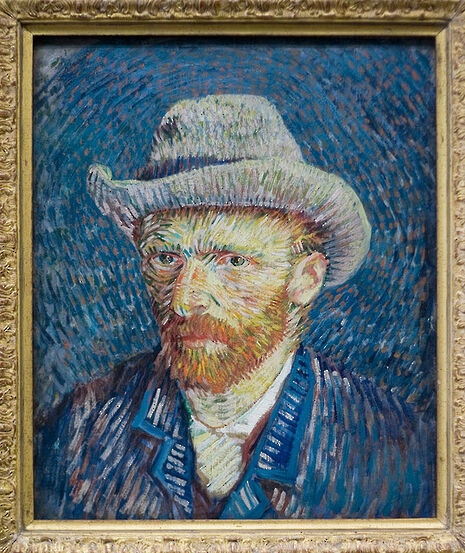

It seems that, if these fifty paintings, thirty-two etchings and seven drawings were to be gathered into one room, a sort of seventeenth-century time-lapse would unfold, not just of the ravages of age, but of mind, wealth, and artistic technique. Van Gogh, one of the most prolific self-portraitists of all time, painted close to thirty images of himself in just the last three years of his life. Again, these works display a constantly curious talent, experimenting with brush-stroke and palette, but for some, it is difficult to ignore the pared down quality of the final four, his piercing dark eyes staring out from a pained face tinted green with sadness.

One could, of course, read these forays into self-portraiture as merely documentary; a means of mapping the ever-deepening forehead furrows and receding hairlines, or in the case of a certain Mr van Gogh, number of ears. But with the most famous examples, it is difficult not to feel a more poignant, searching quality in their chronic self-reflection. Such works present us with the key line of questioning when regarding self-portraits: to what extent can we ever be objective when looking at ourselves, and, do we really want to be?

This tension between subjectivity and objectivity would become key for a lot of female artists, especially those working within the growing women’s art movement of the 1970s, begun in the United States by Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro. The self-portrait had been a common subject matter for female artists for centuries, due simply to the fact that, with restricted working resources, frequently the only available model was themselves.

Photography had also become a popular medium for female artists since it had yet to be fully subsumed into a male dominated canon, allowing a sense of greater potential to carve out new ground for themselves. Yet, for some feminist artists, the photographic self-portrait became a politicised weapon. Susan Sontag would publish On Photography in 1977, writing that "While a painting or a prose description can never be other than a narrowly selective interpretation, a photograph can be treated as a narrowly selective transparency. But despite the presumption of veracity that gives all photographs authority, interest and seductiveness, the work that photographers do is no generic exception to the usually shady commerce between art and truth." It was clear to many that, despite its aesthetic of documentation, photography was just as susceptible to subjective manipulation as any other art form.

Many female artists responded to the bombardment of advertising images adopting the male gaze by turning the lens on themselves. Both Cindy Sherman and Gillian Wearing would, and continue to, utilise the self-portrait to explore the manner in which women are perpetually sold the concept of re-invention and ready-made identities, reducing them to two-dimensional cartoons, but also encouraging their participation in a game of deceit. By donning disguise, the resulting, highly constructed images are in someway surreally threatening and highly conscious of the response they would provoke in the viewer.

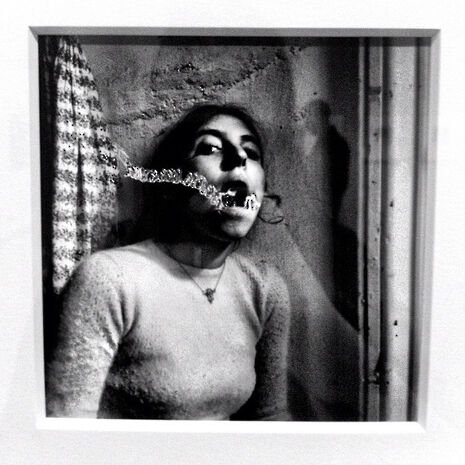

Other artists, however, would respond to this problem in a quieter, more personal, way. One of my favourites, Francesca Woodman, would dedicate her short and troubled life to producing hundreds of black and white photographs of herself. Usually choosing to set her works in crumbling, deserted buildings, and often presenting herself partly, if not fully, nude, her work is intrinsically connected to a study of her gendered body. Frequently using movement, long exposures and hiding parts of herself, her oeuvre presents ghostly image after image. Yet Woodman is not naïve. She was clearly highly aware of the seductive qualities of her body; she curls up next to eels that mirror the curve of her hips and crouches on a dusty floor wearing only a cropped sweater. She looks up at a camera looking down, thrusting upon the viewer a disparaging gaze of control.

It is this idea of control which has led to many contemporary commentators citing the selfie as a feminist act, one in which young women present the world with an unapologetic and celebratory image of themselves. This seems to make sense when considering selfies whose subjects exist outside of normative standards of beauty. But the inter-congratulatory nature of the manner in which the selfie is shared, and their existence within the context of a patriarchal society, break down this analysis; the insistence upon adding every tumblr-girl’s tagline #nofilter says it all.

Artists have been taking less constructed self-portrait photographs for years, too. Alexis Hunter’s Self-Portrait, 1977, or several images from AA Bronson’s Mirror Sequences, arguably could have been taken by any one of us armed with a camera and a little know-how. And still, the relationship between self-portraits and the selfie becomes ever more complicated when we move beyond the boundaries of the 'official' art world and look at images presented outside the gallery space. Ai Weiwei, a Chinese artist who has been under constant surveillance by his government since April 2011, has been using Instagram to share smartphone images of himself since it began, and he is by no means the only contemporary artist to do so.

Are the images he shares art? They are often aesthetically pleasing, but require no more technical knowledge to produce than any other amateur smartphone photographer. But prior to Instagram, his personal blog was shut down multiple times. His insistence on visually communicating with the world by any means he can changes our reading of these selfies into a rebellious act. Regardless of whether we can call a selfie art, it cannot be coincidence that time and again, humans choose to turn the focus on themselves.

Perhaps, if Descartes is to be believed, the selfie is a 21st century case of 'I Instagram, therefore I am.'

News / Police to stop searching for stolen Fitzwilliam jade17 April 2024

News / Police to stop searching for stolen Fitzwilliam jade17 April 2024 News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024

News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024 Interviews / ‘It fills you with a sense of awe’: the year abroad experience17 April 2024

Interviews / ‘It fills you with a sense of awe’: the year abroad experience17 April 2024 News / Night Climbers call for Cambridge to cut ties with Israel in new stunt15 April 2024

News / Night Climbers call for Cambridge to cut ties with Israel in new stunt15 April 2024 News / Acting vice-chancellor paid £234,000 for nine month stint19 April 2024

News / Acting vice-chancellor paid £234,000 for nine month stint19 April 2024