Visions of the forty-fourth president

As we approach the American election, Ameya Tripathi considers how artistic representations of electoral candidates have changed over time

Last month, Los Angeles street artist Saber took to the skies to protest Mitt Romney’s promise to cut arts funding for the National Endowment of the Arts, National Public Radio and the Public Broadcasting Service. Working only from donations, Saber wrote ‘Defend the Arts’ using a small plane over the Manhattan skyline. This was an imitation of a previous stunt where a Los Angeles law banned graffiti. Saber responded with skywriting. The act symbolises how Saber and other artists are being pushed to the margins; having to fly to display their message because society would not accommodate them on the ground below. The feeling of ostracisation and being on the back foot is what characterises the art of the US 2012 election, in a very sharp departure from the strident and hopeful art of four years ago.

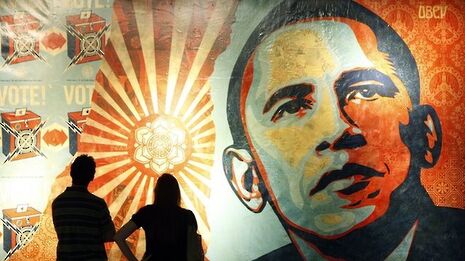

Everyone remembers the ‘Hope’ poster of Barack Obama that became widely used in 2008, on buttons and badges, in university dorms. It was one of the iconic images of a time that already feels immensely different to our own. The difference between Saber’s skywriting and Shephard Fairey’s ‘Hope’ poster is one of tone. One is positive, strident; the other is a negative, scowling take on Mitt Romney’s agenda. The mood has shifted from spreading hope to avoiding despair. The art is anti-Romney much more than it is pro-Obama, and there is less of it.

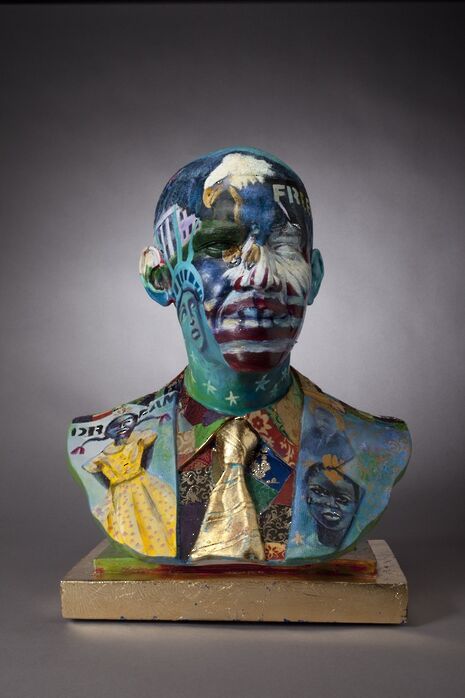

Part of the reason why there has been less art in the 2012 election is not just because there is less enthusiasm but because both candidates are harder to pin down. Barack Obama is a much more complex figure than he was four years ago, varying between professorial and messianic, and it is this dual valency that has quietened the pro-Obama artistic movement. In Detroit, a new exhibition, ‘Visions of our 44th President’ has commissioned 44 African-American artists to work on identical busts of the President. The massive variety is not only a reflection of their individual creativity but of the multiple ways in which Obama is viewed. One bust has him covered with civil rights leaders of the past such as Ida B. Wells and Martin Luther King; another dubs him ‘AmeriKenyan’ in a proud reply to the Tea Party’s continuous accusations of his ‘otherness’; a third covers him in cuttings from the 2008 election night, binding him to the hopeful figure he was in 2008 but also showing how his glory has faded in old newsprint. The exhibition was not for any particular social or political purpose - it was delayed and originally was not meant to be opening so close to the election. While it presents a compelling diversity, Obama’s campaign team have by contrast struggled to find one iconic image that ‘sticks’ as he varies so greatly in personality.

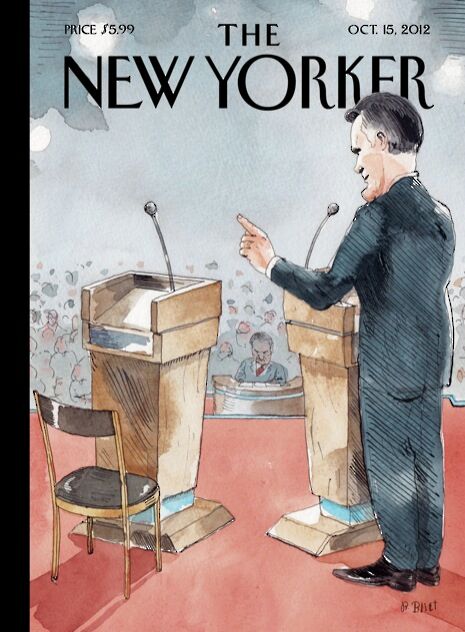

A similar problem of ‘dual valency’ affects the news media and campaigns when trying to depict Mitt Romney. The difficulty in portraying both the candidates is shown by the most recent covers of The New Yorker. After the first debate, in which Obama has himself joked he was ‘napping’, The New Yorker portrayed him as such. That is to say, they did not bother to offer a depiction at all. There were no chairs at the debate in Denver so the chair appears to have been put in to represent the seat of the incumbent who hasn’t turned up, as well as to Clint Eastwood's bizarre lecturing of Obama-as-a-chair at the Republican National Convention - Romney for example does not have a chair. But the cover offers little by way of portraying Romney either. The hand points to nothingness, as if to say, ‘I am here, I turned up’ and not much else. Lehrer, the moderator, looks inattentive and while the spotlights suggest great national interest, the drab gray crowd suggests an unimpressed and uninterested audience.

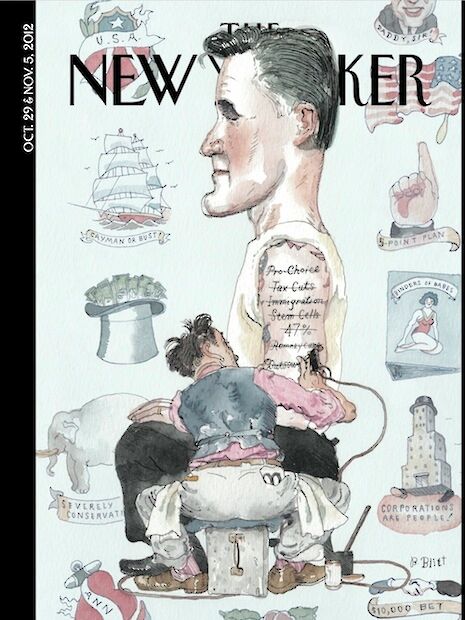

The next week The New Yorker cover got to the heart of the difficulty involved in portraying Mitt Romney and again entirely avoided a depiction of Obama. If Obama is hard to capture because he has gone from a bright-eyed liberal to a pragmatic centrist, Romney is even more so, having veered from moderate governor to severely conservative in the Republican primary to attempting to appear a moderate again. The crossed out tattoos combined with a sea of conservative sentiments (such as ‘corporations are people!’) is very different from Norman Rockwell’s ‘The Tattoo Artist’ from which it is based. Rockwell, who’s famous ‘Freedom of Speech’ endures as an image of the power and hope of democracy, is here used to great satirical effect. Whereas in ‘The Tattoo Artist’ it is the names of girlfriends that are being crossed off, here it is Romney’s commitments on positions that affect millions of people.

The same ambiguity does not exist in Britain. We are a part of a more satirical political culture. There is no pretence of seeing a leader as someone able to deliver a sea-change or revolution - Ed Miliband famously says he would rather 'under-promise and over-deliver'. Steve Bell, the Guardian cartoonist, has been merciless and cynical. David Cameron's head is encased in an inflated condom, Bell describes Ed Miliband as 'a walking caricature even before you've picked up a pen' and Nick Clegg is a butler to Cameron. Political art in the UK brooks no illusions about the capability of politics to effect change; in America, the disillusionment with political gridlock is newer and more palpably felt as the frustrated New Yorker covers suggest.

Is one artistic tradition more or less beneficial than another? Perhaps in the search to create something that feels 'true', Steve Bell's depictions risk perpetuating apathy by evincing our feelings about politicians so precisely. His is a more descriptive practice than the prescriptive and more direct art in the United States, from skywriting to magazine covers which celebrate the President supporting gay marriage. America seems to have an artistic culture which is more productive of social change. So while we may mock efforts such as Fairey's 'Hope' poster (can you imagine any of the British party leaders becoming icons in that way?) it, and the political art of America in general, seems to be one which is more likely to produce change rather than to portray our own condescension.

News / Police to stop searching for stolen Fitzwilliam jade17 April 2024

News / Police to stop searching for stolen Fitzwilliam jade17 April 2024 News / Night Climbers call for Cambridge to cut ties with Israel in new stunt15 April 2024

News / Night Climbers call for Cambridge to cut ties with Israel in new stunt15 April 2024 Interviews / ‘It fills you with a sense of awe’: the year abroad experience17 April 2024

Interviews / ‘It fills you with a sense of awe’: the year abroad experience17 April 2024 Sport / Kabaddi: the ancient sport which has finally arrived in Cambridge17 April 2024

Sport / Kabaddi: the ancient sport which has finally arrived in Cambridge17 April 2024 Features / Cambridge’s first Foundation Year students: where are they now?7 April 2024

Features / Cambridge’s first Foundation Year students: where are they now?7 April 2024