The Good Immigrant: BAME voices in post-Brexit Britain

Danielle Cameron discusses the talk by Darren Chetty, Vera Chok and Coco Khan at the Cambridge Literary Festival

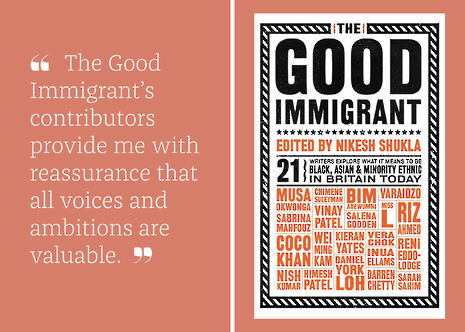

The Good Immigrant was published three weeks after the EU referendum, amid continuing Brexiteer victory dances. Edited by author Nikesh Shukla, the book is an anthology of twenty-one voices exploring what it means to be black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) in Britain today. The Good Immigrant is a much-needed antithesis to the longstanding, insidious rhetoric surrounding ‘immigrant’ that the Leave campaign so keenly capitalised on. From authors to actors, the contributors’ biographies provide vital examples of people of colour thriving in numerous fields. The Good Immigrant’s contributors provide me with reassurance that all voices and ambitions are valuable. Three of these contributors spoke as part of the Cambridge Literary Festival 2017 and their presence created an evening of rich, energising and unapologetically direct conversation.

The absence of an external chair on the panel was refreshing and enabled an immediate sense of ease. Darren Chetty, Education PhD student and former primary school teacher, opened the evening with the question of how he, Vera Chok and Coco Khan had become involved with The Good Immigrant. All three expressed how social media, namely Twitter, had played an undeniable role in connecting them with the project. Chok, actress, writer and performance maker, emphasised just how valuable online conversation had been for her as she was the only one not to know Shukla already. Furthermore, the book itself was entirely crowdfunded and reliant upon similar online dialogue and interaction. Khan, journalist at The Guardian, mentioned that “Nikesh (Shukla) is all about diversifying publishing” and fighting against the numerous reasons why there are still startlingly few people of colour working in the arts. While the proportion of people of colour working in the arts remains disheartening, their stories were testament to how the publishing industry can be disrupted from the bottom-up: if an industry is not listening to you, your use of social media can make people listen.

Of course, the connectivity afforded by social media is a double-edged sword. Part of Shukla’s motivation to create The Good Immigrant was a person’s assumption that, as the writer of and most of the contributors to a Guardian article were Asian, writers of colour must all know each other. However, as Khan mentioned, some of the contributors did know one another and, as a result of its production, the twenty-one writers now all definitely know each other. While Khan struggled to break from circular musings upon the problem of nepotism (which, after all, is rife in many industries), she emphasised how “no one would question the nominees for the Booker Prize… no one would say ‘they’re all white, they must know each other’ “. “This,” she continued, “is an example of how when people of colour achieve anything, they must be hyperscrutinised… everyone wants to know what we have and why we have it”. The community of writers created by the movement to get The Good Immigrant out into the world speaks of collaboration and, indeed, a bit of nepotism, enabling artists of colour to release work that calls out this ‘hyperscrutiny’ for the racialised accusation that it truly is.

Before the event started, the audience were told that Chetty, Chok and Khan wished for the evening to truly be a conversation. Fittingly, the most resounding dialogue occurred in the question and answer session in the latter half of the event. Seeing these writers of colour sitting centre-stage at the Old Divinity School and hearing them speaking frankly about the otherwise little discussed harassment endured by Chinese communities across the UK, sexual politics, and the need for narratives both about and for children of colour was not just a highlight of this year’s festival but a highlight of my time at Cambridge.

Their frankness continued throughout their answers to the audience’s questions that ranged from the future of the project to questions about prejudices existing between different waves of immigration. When discussing the role of the Empire and the Commonwealth in attitudes towards Britain, Chok spoke of her upbringing in Malaysia and of how those moving there envision "a land of smiles with an M&S on every corner” before pausing and bluntly stating “that place doesn’t exist”. Her last statement seems obvious as soon as it is spoken but as has been seen time and again so many communities, including those who want to close the country’s borders, are pursuing a Britain that simply does not exist.

The event closed with a discussion of the importance of respecting all life experiences. Chok also spoke of how the distinctness of the twenty-one stories in The Good Immigrant “is not confined to only ethnic minority communities” and told the audience to “go outside and ask the first twenty-one people you see about their lives, you would totally find the same richness”. Chetty summarised the power of The Good Immigrant when he spoke of how uniting BAME writers together sees a “fracturing” of the monolith that is “non-white experience”: this power lies in its respect for story-telling and encouragement for dialogue. For, as this event, this book and these speakers attest, dialogue is an essential tool in revealing and ameliorating the state of Britain today.

The Good Immigrant is now available from Unbound Publishing (Hardback £15, paperback and audiobook released 4th May)

News / Night Climbers call for Cambridge to cut ties with Israel in new stunt15 April 2024

News / Night Climbers call for Cambridge to cut ties with Israel in new stunt15 April 2024 News / Cambridge University cancer hospital opposed by environmental agency12 April 2024

News / Cambridge University cancer hospital opposed by environmental agency12 April 2024 Features / Cambridge’s first Foundation Year students: where are they now?7 April 2024

Features / Cambridge’s first Foundation Year students: where are they now?7 April 2024 Comment / UK universities are sacrificing widening access for foreign fees11 April 2024

Comment / UK universities are sacrificing widening access for foreign fees11 April 2024 Film & TV / Dune: Part Two is a true epic for the ages11 April 2024

Film & TV / Dune: Part Two is a true epic for the ages11 April 2024