Bedroom Art: teenage kicks

In this week’s column, Ruby Reding interviews Carey Newson, curator of the ‘Teenage Bedrooms: like a house inside a house’ exhibition, to discuss the significance of adolescent space.

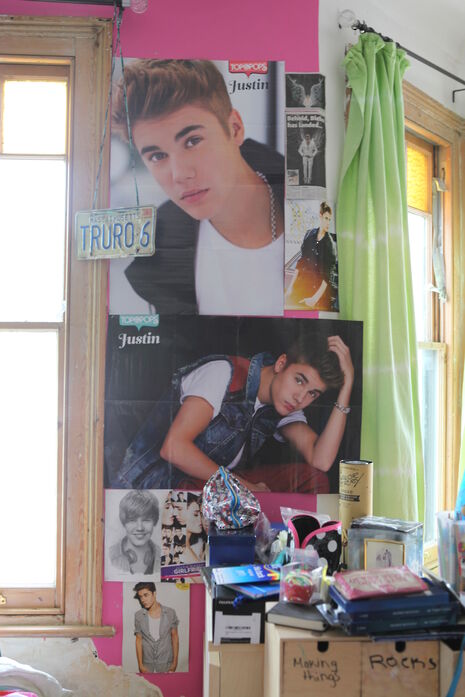

Teenage bedrooms have become a sort of cult image – a place for physical and material representations of identity and experience. The inbetween stage of being an adolescent has only become the phenomenon that we know today in the last seventy years – the very word ‘teenager’ first gained momentum in the 1940s. Representations of teenagers frequently fail to surpass stereotypes. The messy bedroom, the boy-band posters, the futuristic, digital world they supposedly live in, the poorly parted side-fringe – all tropes that present a clichéd image of what a teenager is and should be are entwined with the physical space they inhabit.

Visual representations of teenage bedrooms might bring to mind Adrienne Salinger’s 1990s photographs that have made a recent resurgence online. The stuffed animals and Polaroid photographs are paired with character stories that humanise the iconic pictures. Their popularity today echoes the Tumblr aesthetic of nostalgia. But perhaps not all teenage bedrooms follow these trends.

“For me, this exhibition is a bit like immortalising memories from my teenage years.”

Now displayed in East London at the Geffrye Museum is a small exhibition titled Teenage Bedrooms: like a house inside a house. I spoke to Carey Newson, who curated the exhibition as part of her research for a PhD, to ask her what first interested her about the bedroom and all things in-between.

The display is divided up thematically. The nostalgia of old bedrooms is one of the themes explored in the exhibition, and it is also what she found quite surprising about her research. She said that one surprise was teenagers’ enthusiasm for non-virtual forms of communication – such as letters sent through the post, Polaroid photographs, vinyl records and a manual typewriter, which, she says, “were valued not just as retro objects but for offering ‘tangibility’ in a digital age.”

She adds: “This is not to say, of course, that teenagers were deserting their laptops and tablets, though one participant had taken to doing her homework on a typewriter.”

In the exhibition, artefacts are in the display in glass boxes, such as shoes made from a friend, frozen in time. For me, this exhibition is a bit like immortalising memories from my teenage years.

When I asked Newson how much the teenagers she interviewed allowed her to see the rooms in their natural mess, she replied that she “didn’t want to pander to a stereotype by insisting that we photograph teenage rooms at their most chaotic”, and I think that’s pretty cool, the fact that she “left it up to the teenagers, as the ‘curators’ of these spaces, to decide how much they wanted to tidy up.”

Though always messy and the epitome of what Newson describes as a ‘floordrobe’, my own teenage bedroom was always slightly lacking of an assertion of identity. I have moved homes a total of eight times. This meant that I lost a lot of possessions or usually had cardboard boxes strayed around the room. When Carey Newson visited my art lesson in sixth form four years ago, searching for participants for her research and exhibition collaboration, I mostly thought that my bedroom would not suffice as interesting research, as I had lived in it for three weeks and it didn’t feel like my own space.

My friends and others’ bedrooms, however, made for interesting research. I ask Newson where the initial inspiration for this project began: “It began with teenagers I knew – the teenage children of friends. I was fascinated by the improvised way they were putting their lives on their walls, mixing music, art and political comment with more personal material: doodles, snapshots, even fragments of conversation.”

But Newson’s research isn’t just personal: “I’m also interested in the material culture of domestic space more broadly – the way we assemble things around us through a mixture of accident and design.”

This investigation into the way we use space, and particularly teenagers, is what I found so fascinating about the exhibit. Surely the internet has really shaped and changed the way we conduct our lives in private space? Newson thinks that it has made the bedroom “a more attractive place to retreat to”, adding that “parents in the study saw social media and internet access as the main source of generational difference in teenage rooms. They commented that teenagers now go to their rooms to talk to their friends – making the room a more intrinsically social space.”

Given the isolated and lonely trope of the teenager in the digital age, only communicating online, I thought this was an interesting addition to the conversation. A lot of digital and social media artists frequently explore the adverse – webcam images and ‘so sad today’ tweets about loneliness. But perhaps the larger amount of time that teenagers in Newson’s study spent in their bedroom accounts for this.

“Perhaps, then, adolescence is as much a time for blooming gender normativity as it is also a resistance to it.”

I asked if gender contributed to whether the teenagers used the space differently, since there were significantly fewer boys in the exhibition.

“There was considerable discussion in some of the interviews with teenage girls about the idea of girliness and a changing relationship over time with overtly feminine things they had rejected earlier: flowery dresses, perfume, the colour pink,” says Newson. “Some girls’ rooms reflected a commitment to feminism, for instance in feminist graffiti or artists seen as feminist role models.” Perhaps, then, adolescence is as much a time for blooming gender normativity as it is also a resistance to it.

Most interesting to me, however, is the transcendent nature of the bedroom, and the exhibition’s placement of the bedroom in a historical context – quotes from parents about their experiences of private space feature in the exhibition. The bedroom, or even the decoration of the personal space where we sleep, is a predominantly relatable concept. In the Geffrye Musuem, quotes from parents about the differences in their own teenage bedrooms line the walls of the display. Walking around the exhibit, the most notable element of how people at the gallery were responding to the project was the discussion of their own teenage spaces. Resonating the history, nostalgia and universal nature of the bedroom, one annotation breaks the ‘fourth wall’ in the exhibition, asking “What are your memories of teenage bedrooms?”

News / Police to stop searching for stolen Fitzwilliam jade17 April 2024

News / Police to stop searching for stolen Fitzwilliam jade17 April 2024 Interviews / ‘It fills you with a sense of awe’: the year abroad experience17 April 2024

Interviews / ‘It fills you with a sense of awe’: the year abroad experience17 April 2024 News / Night Climbers call for Cambridge to cut ties with Israel in new stunt15 April 2024

News / Night Climbers call for Cambridge to cut ties with Israel in new stunt15 April 2024 Sport / Kabaddi: the ancient sport which has finally arrived in Cambridge17 April 2024

Sport / Kabaddi: the ancient sport which has finally arrived in Cambridge17 April 2024 Features / Cambridge’s first Foundation Year students: where are they now?7 April 2024

Features / Cambridge’s first Foundation Year students: where are they now?7 April 2024