Put your pens away: the V&A bans sketching

Why should ‘Undressed’ remain undrawn?

The decision to ban sketching at the V&A’s ‘Undressed: a brief history of underwear’ exhibition is sheer pantaloonacy. It might even be more provocative than some of the garments on display.

The museum has justified the ban partly by suggesting that sketchers create unnecessary congestion, apparently upsetting the metronomic pace the V&A has set for the masses. But, surely, if you’re going to make a point of exposing something which would otherwise be private, intimate, and ever so slightly naughty, it seems contrary to enforce an all too brief encounter.

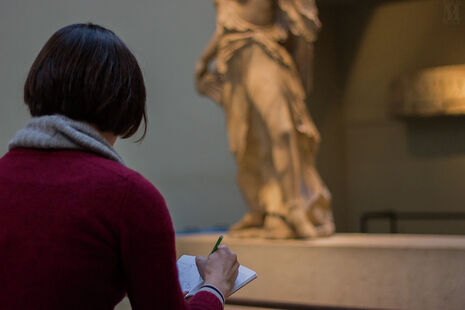

But what really gets my knickers in a twist is that the V&A’s sign, ‘No photography or sketching’, tars photos and drawings with the same brush. Both, of course, can be forms of art, but in a museum context, one feels more obtrusive than the other. Aside from the clicks and flashes of cameras, there is always the temptation to hide behind a lens, to capture something passively without really engaging with it. But to draw something, you have to open your eyes. Sketches are sexy. They leave something to the imagination, showing more and less at the same time. A sketch is never an exact copy, but an interpretation.

By banning people from sketching, the V&A risks trivialising its own exhibition. Of course, you might argue that an exhibition whose highlights include photos of a scantily clad David Beckham for an H&M campaign or Kate Moss’ famously see-through slip dress might not purport to be anything but trivial. But, even if this is true (and I’m not convinced that it is), why shouldn’t it be celebrated, or even transformed, by art? Andy Warhol found his inspiration in a tin of Campbell’s tomato soup. Who’s to stop someone finding theirs in Jaeger woollen underwear or in the pants of Queen Victoria’s mother? In fact, Warhol was once so enamoured by Jockey briefs that he used a pair as a canvas for one of his dollar-sign paintings. Whether it heralds the everyday, the saucy, or the soupy, art’s very foundations lie in a freedom of interpretation which would be dangerous to jeopardise.

The museum was quick to point out that the ban would only apply to certain temporary exhibitions, and that sketching in the permanent collections was still welcomed. But could the move be suggestive of a wider hostility towards drawing in art galleries? While at the ‘Rembrandt: the late works’ exhibition at the National Gallery last year, I was told to stop sketching because I was being inconsiderate towards the other visitors. I was surprised; I’ve sketched in a lot of galleries and people are generally more interested than annoyed. Personally, I love having a peek at other people’s sketches; in the case of Rembrandt’s self-portraits, they allow you to see what others make of Rembrandt as well as what the artist made of himself. The creation of multiple dialogues can only be a good thing, and in suppressing them, galleries are at risk of alienating the very people they should be encouraging. As one disgruntled art-lover tweeted in response to the V&A ban, “No memorising anything you see. Approved memories can be purchased in the gift shop”.

But perhaps the saddest thing about keeping drawers and drawings apart is that, historically, the two share a deep affinity. In the 18th century, underpaintings and undergarments existed to be covered up. Neo-classical art was characterised by meticulous control and precision, and, at that time, sketches were simply a means to an end, remaining hidden away in artists’ studios. Similarly, just as sketches would provide the architecture for a painting, painfully restrictive whalebone corsets would (almost literally) provide the architecture for women’s sumptuous dresses, but were never to be seen in public themselves.

Since that time, underwear has become outerwear, and sketches have become masterpieces in their own right. It was not until the late 19th century, when interest in outdoor sports grew, that the marketing of the “sports corset” allowed women to exercise en plein air. And it was around the same time that the likes of Monet, Pissarro, and Sisley ventured outside, making quick, lively sketches which caught changing patterns of light and movement, capturing the bustle of the modern city or the tranquility of the modern garden.

Embracing a looser, more personal style, both art and underwear allowed for a little more room to breathe. But in both cases the transformation was controversial. For many, the idea of undergarments becoming more fashionable than functional was utterly contemptible. And at the Impressionists’ first exhibition in 1874, which included Monet’s famous ‘Impression: soleil levant’, the critic Louis Leroy sneered at Pissarro’s ‘palette-scrapings placed uniformly on a dirty canvas’, deploring the group’s ‘mudsplash’ brushstrokes and their lack of ‘respect for the masters’. This modern art was as crude and obscene to Leroy as sexy, revealing lingerie was to conservative critics.

Now, of course, lingerie and underwear can be fashion statements as well as commodities, and sketches and drawings are celebrated alongside paintings and sculptures in galleries.

Given that both sketches and underwear have experienced something of a parallel emancipation, it is a shame that ‘Undressed’ only celebrates freedom of expression and daring creativity on one side of the exhibition glass.

Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024

Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024 News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024

News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024 News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024

News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024 News / John’s spent over 17 times more on chapel choir than axed St John’s Voices22 April 2024

News / John’s spent over 17 times more on chapel choir than axed St John’s Voices22 April 2024 News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024