China’s silent war on bloggers

Is China’s increased internet censorship a return to Tiananmen-style authoritarian crackdowns? Frederick Green voices his concerns.

For many in China, the deep rumble of tanks at Tiananmen Square doesn’t seem so long ago. There, students held up stark red banners, chanted, cooked and marched together, all in the name of reform. A threatened Communist leadership, fearful for its grip on power, would not accede, and troops were called in.

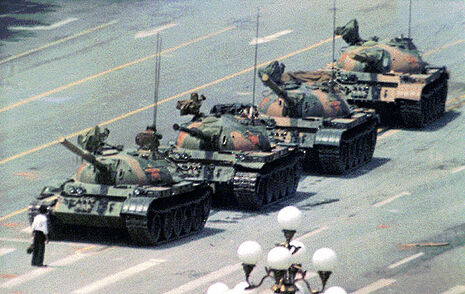

The only thing more terrifying than the events at Tiananmen is the notion that it could happen again. A new change in law, permitting the direct arrest of controversial internet bloggers, has uneasy parallels. What’s more, while images of a protestor defying a row of tanks circulated on TV screens around the world in 1989, this blow to freedom of speech has received alarmingly little international coverage.

An existing law has been expanded to give authorities the power to arrest microbloggers who spread malicious online “rumours”. The New York Times anonymously quotes an official who claims that the government’s purpose is “draining toxic lies from the internet.” Needless to say, such ambiguous terminology gives the internet police free reign.

Supposedly, if an individual’s post is seen more than 5000 times, or is re-posted more than 500 times, police may come knocking on their door, and maybe even invite them for a “cup of tea” (an idiomatic prelude for detention). Cells that should be filled with rapists, murderers, and corrupt politicians are instead being crowded with Netizens, sometimes in their teens. In September, sixteen-year-old middle school student Yang Hui was interred in Gansu province for questioning local police’s political motivations online.

Yang is part of a new generation of students forged in an explosion in the Chinese middle class. They are often well-informed, well-educated (sometimes in the West) and hungry for change. They bear resemblance to the students of 1989, who grew up in a time of increasing economic prosperity, and of increasing exchange with the West.

The ’89 students took pride in their university organizations, which called for reform and criticised those aspects of Communist rule that remained draconian. Those of today are technologically competent, and have taken to the internet to voice their grievances. They are a demographic that have grown up with, and understand, the internet’s potency as a force for change.

And they have used it skillfully. For the last few years, young Netizens and journalists have been the downfall of various corrupt politicians. Take the recent case of Liu Tienan, a high-ranking economic official known for demanding substantial bribes. A formal allegation of corruption levelled against him by a journalist on microblogging site Weibo was reposted by thousands of enraged internet users. The government responded by sacking Liu in August. For the government to cede to the vox populi is a breath of fresh air, even in the toxic cauldron of Beijing.

So it’s wrong to think that the Chinese government is working on a different wavelength to its people. The ’89 government’s ears were much more attuned to student voices than those of previous regimes. Similarly, today’s government is willing to make the occasional concession. Sacking a corrupt high official over here might seem like a natural state of affairs, but for a Chinese government obsessed with “saving face” and looking like a genuine superpower, this is monumental.

For a while, it seemed as though President Xi Jinping would remain faithful to his early promise to “always listen to the voice of the people” and root out corruption. His inaugural speech to the 2013 National People’s Congress in Beijing, albeit robotic, was stern and sincere, and instilled some observers with genuine hope. Yet politicians rarely keep all their promises, and last month’s change in legislation stands testament to that.

But if only this was a simple case of broken promises, as in Western governments. Sadly, the problem runs far deeper. Both the regime of the late ‘80s and that of today will only condone reform for so long. Sometimes, simple concessions and changes won’t suffice. Tiananmen Square proved to the authorities that largely independent protests, with various different goals, can quickly mould into one.

For the same to happen today is not wholly impossible. The potential of the internet is as remarkable as it is unpredictable. The influence of social media on the Arab Spring shows us that much. No Chinese blogger would be reckless enough to mount a direct challenge to the government on Weibo. But cases of corrupt officials, pollution scares and police scandals circulating online can quickly transform into something much more coherent. They can unite people, often against the government.

The Tiananmen Square crackdown was a terrifyingly public affair, and the violence of that period will, hopefully, never be repeated. The government’s newfound hegemony over the internet, while ominous, cannot be considered on the same level. Nonetheless, parallels exist, and the consequences we have so far witnessed are unsettling. The crackdown we are witnessing today is subtle, precise, and vicious.

Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024

Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024 News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024

News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024 News / John’s spent over 17 times more on chapel choir than axed St John’s Voices22 April 2024

News / John’s spent over 17 times more on chapel choir than axed St John’s Voices22 April 2024 News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024

News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024 Theatre / The closest Cambridge comes to a Drama degree 19 April 2024

Theatre / The closest Cambridge comes to a Drama degree 19 April 2024