Interview: Laurie Penny

Hannah Wilkinson talks to Laurie Penny about the lack of opportunities young people are facing today, and what we can do about it

“Sorry I’ve ranted a bit. I just never get a chance to nerd out about media stuff”.

Laurie Penny needn’t have apologized. I was in my element. Twenty minutes into our interview and she had already smashed two rules that I had been living my life by up to that point. One: Never meet your idols, and two: Chokers are so 1999.

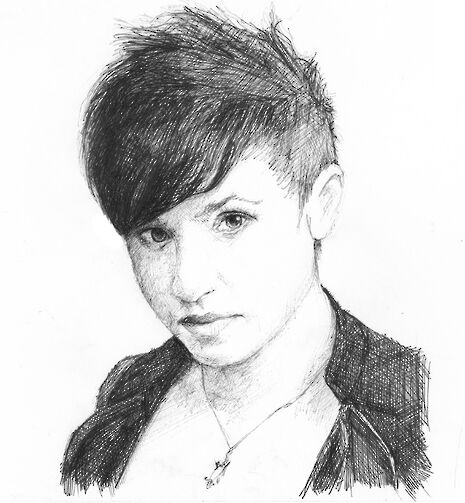

Penny is the bright red hair and 90s accoutrement-sporting contributing editor of the New Statesman, who writes on feminism and social justice with the kind of sass and brains that make her pieces a regular on my Facebook feed. She’s also an author and award winning blogger, but came to Cambridge to debate at the Union because her boss told her she had to. Her unwillingness was not suprising, given that she was going to be arguing on the same team as Simon Heffer - whose speech began with a nod to the “ladies present”.

It’s not that Penny isn’t passionate about the topic. The New Statesman sponsored the Cambridge literary festival, and is contributing to proceedings by debating the motion “This House Believes Baby Boomers Left Society Worse Than They Found It.”

Throughout the interview Penny speaks passionately about young people; their problems, their ideas, their opportunities. But for Penny the most revealing thing was that they had such a hard time finding people to speak in opposition. “Everyone agrees young people are fucked,” she says.

She also resents being seen as a mouthpiece for young people, a group she no longer feels she represents.

“I graduated in 2007 before the crash, and I look at my friends who graduated just after the crash and the difference is just astonishing” She explains. “People my age and older believed that if we worked hard and did all the right things it would all be fine eventually. Now people know that’s bullshit.” Even today’s fifteen-year-olds, trudging down the gloomy path of GCSEs and A-levels, are beginning to realise that the light might not still be there when they get to the end of the tunnel.

“I can’t imagine how angry people must be, and just because they don’t necessarily show it because they’re frightened, and British, and under a lot of pressure doesn’t mean they aren’t angry,” she says. “They know it isn’t going to work out, which is why everyone’s reading the Hunger Games and Divergence and getting ready for the dystopia.”

Instead of fretting about the future, Penny spent her days at Wadham college Oxford performing with the Light Entertainment Society, hanging around in goth clubs, and drinking. She searched for the hot bed of political activity she had expected to find there, but found nothing but “Young Labour and a few Scattered Communists.”

It was only when she recently returned to speak at the Oxford radical forum that she found the radical politics missing from her undergrad days. “People who are at university now are in general more aware, more radical than they were when I was at university seven years ago.”

It’s not that young people aren’t interested in Westminster anymore; Westminster was never interested in them. “Young people are there to stuff your envelopes and bring your tea and do your admin and are not the people who actually matter and it’s all about making young people work for politics.”

Penny isn’t just an angry young woman, bellowing into the internet. Her work is effective and convincing, and her award winning endeavors in blogging show that she’s deeply engaged in how people are using new media to change the kind of voices that get listened to. But an angry and a confrontational debate in a 200 year old chamber is not her idea of how best to do that.

“The whole point of discourse and debate and critique is not to actually learn anything, it’s just to win. Beat the other guy. If you make the other guy cry then you’ve won, and that’s it, that’s all it comes down to just people shouting at each other in a room.”

Although she wishes there were more skilled debaters who really cared for the issues, Penny is unlikely to become one of them. “I was crap at debating at school,” she remembers. “I joined the team and I would just get really over-invested in a topic and cry, and then I would lose. Eventually I was not allowed to do it anymore.”

Even if it meant she could debate abortion rights with Louise Mensch without physically shaking with anger afterwards, Penny has no desire to develop a debater’s “thick skin”.

“I could do, but I’d be a shit writer” she says. “I need to be listening and engaged. The last thing I need is a thick skin.”

Luckily for Laurie, anyone who hates the aggressive medium of the televised debate can now just make a podcast and broadcast their own. “Interesting stuff is happening in the podcast world. People are making discussion shows where people aren’t just yelling at each other. They’re just more in depth, more discursive.”

As a 27-year old in a world where people are increasingly finding new ways to be heard, Penny no longer has to be the voice of the angry young person. “It’s not my job to keep writing on youth issues. Arguing for and about young people is really hard because it’s a genre that changes every year not just in terms of how politics change [but] in terms of how you change.” To prove a point, she shows me a Facebook status posted by a friend the previous night:

“Last night danced semi-unironically to Sean Paul whilst we all discussed how much we regret campaigning for the Liberal Democrats in 2010. Possibly my most millennial moment ever.”

Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024

Interviews / ‘People just walk away’: the sense of exclusion felt by foundation year students19 April 2024 News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024

News / Climate activists smash windows of Cambridge Energy Institute22 April 2024 News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024

News / Copycat don caught again19 April 2024 News / John’s spent over 17 times more on chapel choir than axed St John’s Voices22 April 2024

News / John’s spent over 17 times more on chapel choir than axed St John’s Voices22 April 2024 News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024